Last Updated on

By David Link

I have a good friend who was (and still is) my hiking partner and cohort anytime I want to head out into the wilderness. We both grew up in Illinois and we spent a good chunk of our college days in the beautiful Shawnee National Forest surrounding Southern Illinois University. I remember plenty of days where we would explore the lush forests and rock formations in southern Illinois without much fear of ticks. It’s not that we were oblivious to the potential dangers of Lyme disease, and we both knew that checking for ticks after a hike was important. But it seemed like a rare occurrence, and we were never that concerned it would happen to us, and if it did, we would catch the signature “red bullseye” and seek treatment immediately.

A year after I moved out of the area, my friend started feeling weak and had trouble getting out of bed. After a few days of feeling terrible, he reluctantly headed to the doctor and was surprised to find he was on the verge of a heart attack. He had contracted Lyme Disease, and it was attacking his heart. He had never noticed a bulls eye mark on his body, and there’s question as to whether on ever appeared on his body at all. Luckily he caught it in the nick of time. After he endured several months of daily antibiotic doses through a temporary intravenous implant in his arm, we were both convinced Lyme Disease, and avoiding contact with ticks, was a serious matter.

The thing is, most medical professionals aren’t educated to diagnose Lyme Disease, and often it is mistaken for some other ailment. This is all the more reason to be cautious of exposure to ticks. Now that spring is upon us, it’s time to get serious about ticks if they are found in your area. Here are some tips and gear suggestions to aid in the fight.

A Word On Tick Species

Ticks are parasites that need to feed on the blood of a host to survive. They are common around the world, but they need to live in areas with a decent level of humidity to survive. This means ticks are more often found in lower elevations with warmer climates. Once attached to a host, a tick will continue to feed until they are engorged with blood and release from the host.

There are many species of ticks, and while not all of them are said to carry Lyme Disease, every species of tick can carry some form of infectious disease, and therefore they should all be regarded as dangerous in some regard. Popular US species include:

Wood Ticks / American Dog Ticks

The wood tick is probably the most common tick you’ll encounter, and they are often called dog ticks because you’ll find them hiding in the ears or fur of your dog. These ticks are larger and have a hard shell that makes them easy to distinguish. Wood ticks cannot transmit Lyme Disease, but they can transmit other diseases and even inject a dangerous toxin that causes what is known as tick paralysis.

Lone Star Tick

The Lone Star Tick can be found in most of the eastern United States. Adult females have a large yellow blotch on the top of their shell. These ticks do not transmit Lyme Disease, but they do carry a host of other dangerous diseases including the rare Heartland virus. They can also prompt meat allergies in those who are bitten by the tick.

Rocky Mountain Wood Tick

This species of tick is isolated to only a portion of the western states, and in addition to potentially causing tick paralysis in its hosts, it also carries Rocky Mountain spotted fever and Colorado tick fever. These two aliments can cause a host of uncomfortable symptoms, but Rocky Mountain spotted fever is the more dangerous of the two and can cause lasting effects like partial paralysis.

Deer Tick

This last main US variety of tick may be the most dangerous. This tick species gets their name from being common parasites on whitetail deer, but they can be found on other animals like bears, birds, mice and lizards. Deer ticks are extremely small, and this makes them especially hard to spot. Research suggests that deer ticks are the primary if not the only main transmitter of Lyme Disease. While all ticks are said to carry Lyme Disease, only deer ticks have the ability to transmit it to their host. Transmission of Lyme Disease is a matter of time, and the longer a deer tick is on its host, the more likely the host is to contract Lyme Disease. As I mentioned above, a “bullseye” red mark at the site of the transmission is a common indicator of Lyme Disease, but not every host infected with Lyme Disease displays this mark.

Tick Avoidance

Now that we’re all sufficiently informed (some of us concerned) about what the different tick species can transmit, it’s time to get wise about how to avoid coming into contact with these nasty creatures. First, it’s important to understand how ticks latch onto a host. Ticks cannot fly or jump (thankfully), and they rather try to hitch a ride on a host by hanging out on nearby vegetation with some of their legs stuck out to grab onto the host. Some species will try to extract blood from a host right away while others will wander on the host until they find a warmer area that is less in the open like an ear, armpit or groin area.

It follows that the key to avoiding ticks is to be weary of tall grassy or thick wooded areas. Damp, shaded areas with dense vegetation can also harbor ticks, but sunny, hot areas will generally have less ticks nearby. This is due to how ticks hydrate. Ticks get water through their pores, and a hot or sunny area will dry them out. Using some of the gear listed below when spending any time in high tick areas will help, especially since there’s no way to avoid rubbing up against brush while hiking or working in areas where ticks are common.

Gear For Tick Prevention

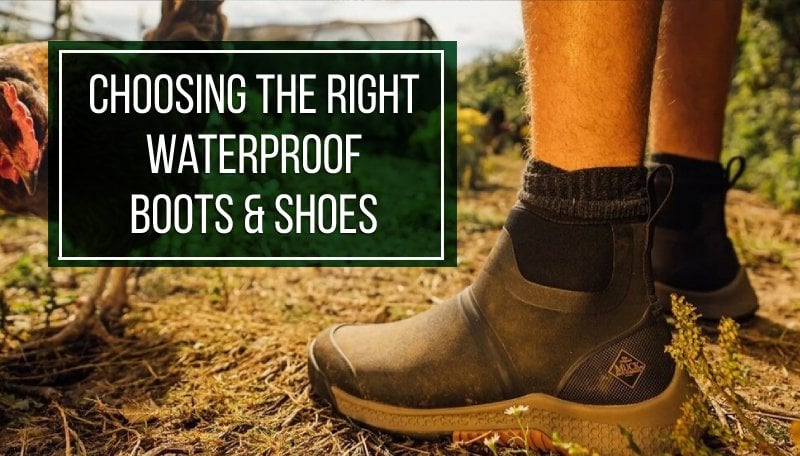

Gearing up for tick prevention starts with a good pair of pants. Nothing is more foolhardy than wearing a loose pair of shorts through a tall grassy field in an area with ticks. Sure, you might say: “It’s summer and I’m going to fry in a pair of pants!” There are times where we all want to hike in a pair of shorts, and I think it’s easier to do that if you plan to stay on a path. However if you’re doing some serious trail blazing or working in a high-tick area, pants are the prudent choice. It’s best to create a tight barrier between your shoes or boots and your pant legs so ticks have a harder time crawling up your leg. A do it yourself method is to tuck your pants into your socks, but some hiking or hunting pants have a Velcro strap at the bottom of the pants to create a similar seal.

Another recommendation comes in the form of clothing color. Wearing light colored clothing will help you or a companion spot a crawling tick, and it might just prevent it from latching onto you. Of course ticks can still slip by unnoticed, but this is a good extra measure for some, especially those hiking with children.

Really the best gear for tick prevention comes in the form of repellent, but don’t just grab the first repellent you see on the shelf and call it good. Ticks are actually resistant to common bug repellents, and you need tick specific repellent that is expressly made for these pesky parasites. The best tick repellent I’m aware of is from ScentBlocker. Their Bug Blocker For Ticks spray can be used to treat clothing, tents and other items, and the treatment lasts up to two weeks. A key area to always spray is the region where your pant legs meet your shoes or boots. This is always a main byway for ticks hitching a ride, and both your pants and boots should be treated.

Tick Removal

One last thing to cover about ticks is how to remove them. First, you’ll need to inspect yourself after spending time in any area that might harbor ticks. Check all areas for any ticks that may have hitched a ride. You should also be careful with the clothing you wore on a hike, and a good tip I’ve heard is to throw them in the dryer for a few minutes right away to fry any ticks. Just tossing these clothes in a hamper may introduce ticks to your home. Finally, I always make it a point to shower as soon as possible after I leave a high tick area on the off chance you might wash a wandering tick away before it attaches.

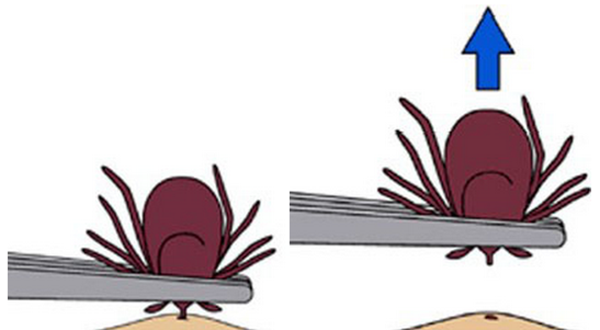

In the event that you find a tick attached to you, the CDC recommends a good old pair of tweezers. The key here is to avoid any additional infection like squeezing tick blood into your body or leaving behind any of the mouth parts. Instead grip the tick at the base of it’s head, and pull directly up. Any squeezing of the tick body or twisting of the tick should be avoided. Don’t wait, the longer a tick is on your body, the more likely it is that you’ll contact a disease from it. Monitor the area for a couple weeks afterward to make sure no rashes or bullseyes appear, and be aware of any unexpected symptoms like significant nausea.

Be safe out there and keep those ticks at bay by exercising caution. That said, don’t be afraid of the woods either. Many ticks do not have diseases, or they can only be transmitted after extended contact. So your best weapon is awareness.

Image one, two and thumb, three, four, and six all courtesy of Wikimedia Commons. Additional research consulted from Wikipedia.