Last Updated on

When it comes to any physical activity, the importance of a functional central core is crucial to performance and avoidance of injury. You might be reading this article because you are curious on just how to improve your “core.” Maybe someone has told you this is important for getting that next PR while you have plateaued, or maybe you are plagued by chronic injuries so you need anything that can assist you in your return to your sport. Core stability is the game changer as it allows you to maximize force generation and minimize the loading on joints across all types of activities. Unfortunately, there is a huge misconception on what the “core” is and the evaluation of it.

What is the Core?

So, what is the core? In terms of musculosketal core of the body, the core is made up the abdominals, but there is so much more involved like the spine, hips, pelvis, and the proximal lower extremities. These muscles in the trunk and pelvis are responsible for the maintenance of the stability of the spine and pelvis. When we talk about maintenance, it is so much more crucial than what it sounds like. The muscles in the trunk, hips, and pelvis help in the generation and the transfer of energy from large to small body parts in various sports. This article will provide a general definition of core stability and describe the anatomy and physiology of the muscles in the core, including its function and dysfunction. We will also touch on rehabilitating and conditioning your core to maximize the effects it has on athletic activities.

The Kinetic Chain

Core stability is defined as the ability to control the position and motion of the trunk over the pelvis. This allows optimum production, transfer and control of force and motion to the muscles in athletic activities.” When a core is stable, it provides maximum stability for distal mobility (legs and arms.) An example of transferring forces is what happens when you run. If you want a higher cadence, it shouldn’t be initiated from just your legs but recruited from the hip, spine, and trunk. The same can be applied to cycling; you don’t want to over compensate using just the smaller muscles of your body but the stabilizing ones of your core to be successful in transferring the energy to a higher wattage during your time trial.

A pitcher like Yu Darvish is not pitching at these high speeds because his arm is really strong, it is because his core is able give his arm energy and force to transfer onto the ball. All these examples describe the importance of the kinetic chain. If you remember that childhood song we all had to sing when learning the bones: “The thigh bone’s connected to the hip bone, the hip bone’s connected to the back bone, and the back bone’s connected to the neck bone,” then you have a basic understanding of how the kinetic chain functions. Injuries such as patellar tendinitis, Achilles tendinitis, tennis elbow, and shoulder pain can all be from an insufficient stable core. The muscles of those extremities are working harder than they need to be to perform certain activities.

Anatomy of the Core

As I’ve stated before, the core acts as the foundation for many movements in the extremities such as the arms and legs. It is a misconception that to work out your core means you should do “crunches and abs” to get stronger and get that six-pack on your stomach. Unfortunately, a six pack will not necessarily help you stay injury free and nor will it maximize the production and transfer of forces during activities in your sport. The point is, the abdominals (rectus abdominus, tranverse abdominus, internal, and external obliques) are in fact part of your core but not the only core muscles nor the most important ones. There are prime movers of the core for distal segments of the body such as the latissimus dorsi, pectoralis major, the hamstring group, the quadriceps group, and the iliopsoas which attach directly to the core of the pelvis and spine. Then there are major stabilizing muscles which consist of the upper and lower trapezius, the glutes, and the hip rotators which also attach to the pelvis and spine.

Physiology of the Core

Unfortunately, you can’t just work on the strength of the muscles involving the core. Sometimes that isn’t even the issue. You might very well be strong in your core, but what good is it if you don’t know how to activate correctly or on time? Muscle activation in the kinetic chain is like the wiring in your body. There are pre-programmed patterns of muscle activation for certain movements and at different forces. These patterns depend on length and force. For example, in a fast arm movement such as a throw, one of the first muscles to activate is your opposite gastrocnemius and soleus (calve) muscle. Then the patterns make their way up the trunk to the arm throwing arm. Another example of these patterns is foot kicking velocity. This is more dependent on hip flexor activation rather than your knee straightening out. These cross-chain patterns can sometimes get out of whack when you have repeatedly been preforming activities wrong, thus, a chronic injury can occur.

Dysfunctions Associated with an Unstable Core

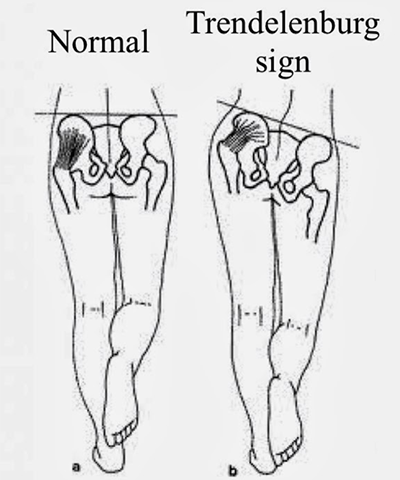

A way to assess for dysfunctions and that are related to core strength is to look at possible weaknesses in muscles in functional positions. A few examples of these tests are as follows: one-leg standing balance ability, one-leg squat, one-leg quarter half squat, overhead squat with a bar, one-leg straight leg raise, trunk stability push up, and a double leg lowering test. For many runners, a typical dysfunction of an unstable core are weak hip muscles. Weak hip muscles result in compensation of the hip and trunk which are commonly associated with knee injuries. If you have pain in the front of your knee, it might very well be because you have weak hip abductors (pushing out) and tight hip flexors.

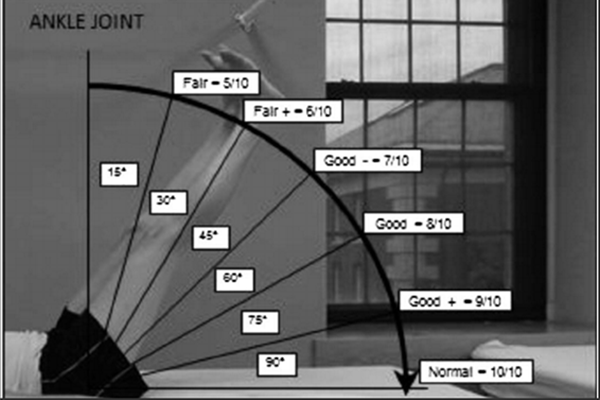

You can also have dysfunctions with the glute muscles. The opposite hip of the leg you stand on will drop and your hips won’t be level. Another weakness may be with the hip abductor. Typically your knee will cave in when you stand on one foot. There are many way to assess for dysfunction. A good indicator is the double-leg lowering test. If you can get past 54% without arching your back as you lower both your legs, it will show you have a decent amount of core strength (see below).

Ways to Improve your Core

Stretching

Going back to the physiology of the core, you may not have a true dysfunction if you have been able to run, bike, swim, throw, or jump. It could just be that the neuromuscular activation of your muscles is not routed correctly. You may just need to teach your muscles to activate at the appropriate times to fix the knee from caving. I know it is constantly said that stretching crucial for an athlete and it is, especially in cases of weak and tight muscles. The muscle activation patterns cannot function for your core if a muscle is too tight to contract correctly. Muscles like the hamstrings, quadriceps, hip flexors, internal and external rotators of the hip, lats, and the rotators of the trunk are good starting points to keep up the maintenance of a good and limber muscle.

The most common static stretches are:

The following static stretches should be done 3×30 seconds on each side after physical activity.

Strengthening

Strengthening of the core sometimes involves a professional being able to explain to you how to abdominally brace. Abdominally bracing involves engaging the muscles of the trunk, hip, and spine while challenging them during distal movements. Strengthening for the core is nothing like doing abs or crunches. It involves a lot of concentration and small, slow movements. To engage these muscles you should still be able to breathe and talk. The easiest way to start is by doing a progression of leg movements while on your back. Abdominal bracing does not mean to just push your back to the and hold your breath while you move. A good way to start and test your core strength is to do these exercises every day. All you need is a table, a gait belt, and a 10-pound weight (8 pounds if you are on the more petite side.)

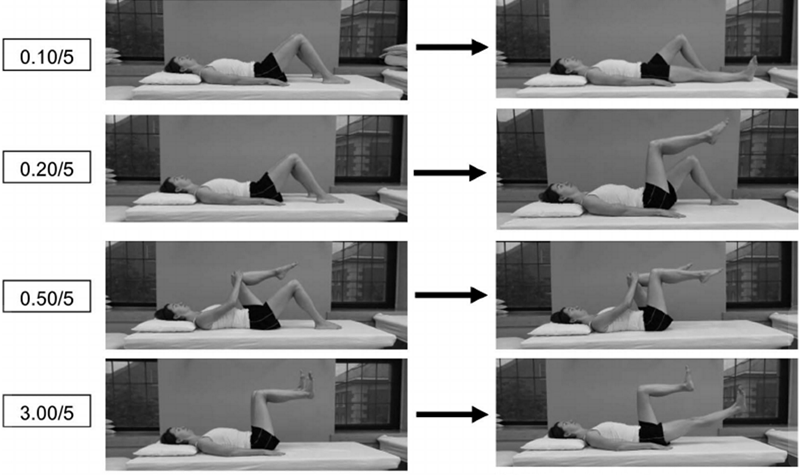

You will place the belt that has the weight tied to it in the small of your back and engage your core by abdominally bracing while challenging yourself with these lower limb movements. A good start would be to do at least 2-3 levels (as described in the figure below) that you can achieve 3×10 a day. Do not be frustrated if you can barely just do level 1. With time, you will progress and really feel a difference in your performance during training. The goal with core stabilization is to really focus on engaging your abdominal brace in functional and challenging movements to eventually being able to transfer that to your actual training and competition.

Conclusion

In conclusion, this article is very brief and only discusses a few ways to start core strengthening. There are many benefits to why you should get a good idea where you are strength wise or activation wise with your core. Sometimes it is just the matter of “waking up” the correct muscles at the appropriate time. It is important to be proactive about your training in other ways than just logging in your miles or making sure you get those track workouts, long rides, and swim workouts. To be a good athlete you must set yourself apart. It eventually takes more than just training and pure talent. It takes stretching, recovery, nutrition, and strengthening.