Last Updated on

By Guy J. Sagi

Experienced outdoorsmen know backups can save lives. Lighters go bad and matches get wet, so somewhere in their kit extras are stored separately in a waterproof container. The same is usually true for flashlights, which can have their batteries die or lightbulb/LED go out. But, what about the device they use stay on trail and find their way back?

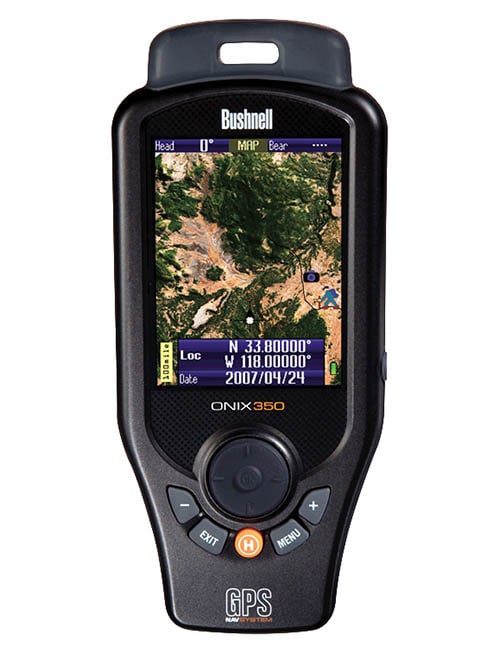

There’s no denying the Global Positioning System (GPS) has revolutionized outdoor sports. It has never been easier to get to and from remote locations, return to the same sweet fishing hole, or explore unknown territory without fear of getting lost. They’re more accurate and reliable than ever before, and most of today’s cell phones come with units and apps on board.

The Achilles heel, we’ve been counseled countless times, is batteries. Carry spares in another waterproof container and the problem is solved, but there are lot of other reasons hikers, hunters and survivalists should have a map, compass and rudimentary knowledge of their use.

Unfortunately, there are a lot of other reasons those miraculous direction finders can fail—and the list seems to grow every day. Here’s a few to remind you why serious outdoorsman always has a compass on hand, even if it’s only for backup duty.

The most common degradation/loss of signal problem occurs when the unit doesn’t receive a direct, line-of-sight signal from the cloud of GPS satellites circling the earth. Everyone’s probably experienced this frustration when following directions from a dash-mounted unit that suddenly gets confused through tunnels or between skyscrapers or hills. Another example is when you move your vehicle’s unit from the dash to the back seat, where the metal roof usually blocks transmissions. The effect can be the same when you’re backpacking through a valley surrounded by high peaks or even camping near a cliff.

Believe it or not, the frequencies used by today’s GPS are not hindered by heavy clouds or rainfall. They knife right through the particles/vapors, but they can’t penetrate even a thin layer of water. Before you breathe a sigh of relief because SCUBA diving isn’t your thing, water soaked into trees above the trail can have the same effect. So does a very thin layer of water atop the receiver, and leaves and trees can get thick enough to jam the transmission, even when they’re dry.

Communications black holes and Mother Nature’s intervention aren’t the only concern. Like everything modern, man meddles.

A National Homeland Security “National Risk Assessment” issued in 2011 (subsequently declassified) provided the kind of laundry list that opened eyes on the vulnerabilities of the entire system. “In the short term, the risk to the nation is assessed to be manageable,” it states in the summary. “However, if not addressed, this threat poses increasing risk to U.S. national, homeland, and economic security over the long term.” Believe it or not, those ATM machines we use at the local bank rely on GPS for time stamps and other duties—hence, one of the reasons for the financial comment.

An electric grid system pioneered shortly after 9/11 harnessed GPS timing accuracy to monitor load demand to react before something unexpected becomes a blackout or brownout. The approach is spreading fast across the country, and despite the entire program being secured by the Air Force, there’s little doubt mercenary hackers will, sooner or later, put it in their sights.

Electronically interfering with systems, both inadvertently and deliberately, however, already occurs. For example, some companies track employees out of the office by GPS. Naturally, that spawned an illegal cottage industry that produces jamming systems. It sounds almost like a victim-less crime, until you consider the fact that the Newark International Airport had one of those systems drive close enough every day for 127 days in 2011 that it temporarily scrambled aircraft ground control signals.

A more devious side to this development is found in those stolen-vehicle recovery systems that rely on GPS. Plug one of these cigarette-lighter-powered jammers in, and the perpetrators disappear in the “noise.” If war breaks out, the ability to help opposing troops “get lost” would be a decided advantage, and that fact hasn’t escaped North Korea’s military. It turned on a signal that affected both military and civilian GPS in 2010. Receivers were effected for more than 60 miles. In 2011 the country did it again, concentrating antennas at Seoul, where even civilian wireless communication felt the affect.

Inadvertent spurious radio interference and jamming are becoming a serious maritime problem, and systems have even been created to “spoof” a GPS unit into thinking it’s communicating with a satellite, when it’s not. If that’s not enough for a prepper to back up his unit, consider the fact that the GPS system is owned by the United States government and its primary mission is military. We get to use two uncoded frequencies to find that distant camping site, but those satellites are also transmitting encrypted and critical messages on different wavelengths across the globe. If the zombies or another nation attacks, expect those civilian-friendly transmissions to end, or at least become so encrypted that only the military and those planes, trains and boats deemed critical to national defense will be issued modern-day enigma machines.

The manmade vulnerabilities in the report are noteworthy, but it’s the more mundane line-of-sight, water and thick-canopy scenarios that imperil today’s GPS-enabled outdoorsman. A compass draws its power from the earth’s magnetic field. If that “battery” disappears, finding your way back home will be the least of your worries.

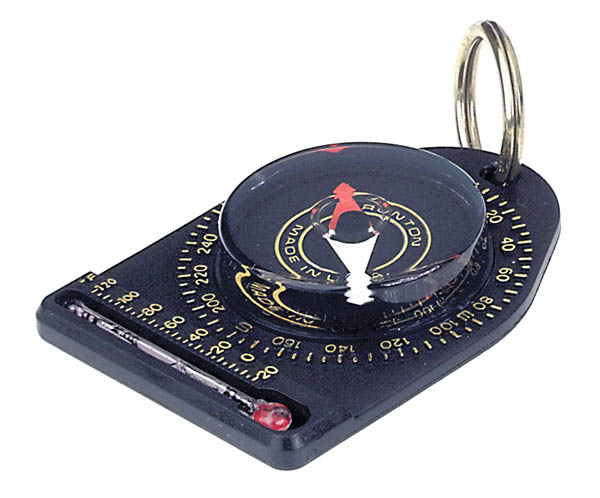

Even the most advanced compass weighs next to nothing, is relatively inexpensive and, with care, lasts for decades. Interference is easily avoided by not taking readings near metal or battery-powered objects, and although it can be spoofed by anything magnetic, walk a few feet and that signal is crystal clear, whether in a thick forest, deep valley or hiding from the zombies in a deep tunnel.