Last Updated on

By Guy J. Sagi

People slightly alter the landscape when they go outdoors, even those of us who make a conscious effort to always “Leave no Trace.” At the very least it’s footprints or scuff marks, but those subtle clues stand out like neon signs to knowledgeable and practiced trackers. Average outdoorsmen don’t have the time to hone those skills to Native American precision, but a rudimentary understanding could help you find your way back to camp in a pinch and provide a lot more information.

Getting lost is scary, even if it’s only a few moments of disorientation while heading back from a distant whitetail stand, chasing convergent lines on a topo map to visit what you hope is a tall waterfall or hunting virtual Pokemon Go characters. If you’re outdoors a lot, though, you know the feeling.

For many, the solution often comes electronically with the use of Global Positioning Satellite (GPS) devices, including your phone. It may be hard to believe for today’s tech-savvy outdoorsman, but there are some not-so-exotic locations where you won’t be able to pick up that orbiting signal. Add Mother Nature’s intervention in cloud cover with spotty cell service and you could be in serious trouble if electronics are your only solution.

You don’t have to go far to experience it, either. This summer—only 3 1/2 hours from my house—I trout fished in an area of North Carolina’s mountains where I knew there was no cell phone service, but when heavy rainstorms closed in, either they, the ridgelines, or combination of both, blocked GPS signals on all of my devices.

The stream made it hard to get seriously lost, but if the unthinkable happened, the periodic tracking lessons I learned from the U.S. Border Patrol during a decade of search and rescue work would have served me well. My skills don’t come close to that of the instructors, but the information they shared helped a lot of outdoorsmen, and still serve me in different ways to this day.

When you can read the landscape—even a little—it speaks volumes. Unfortunately, books, articles and videos aren’t enough to magically make you proficient at tracking. It takes practice.

The good news is, once you understand some of the basics outlined here, you’ll probably catch yourself giving some of them a try the next time you’re out. And if you ever find yourself in a position where you need to confirm which fork in the trail you came from, it’ll pay huge dividends.

Know Your Sole

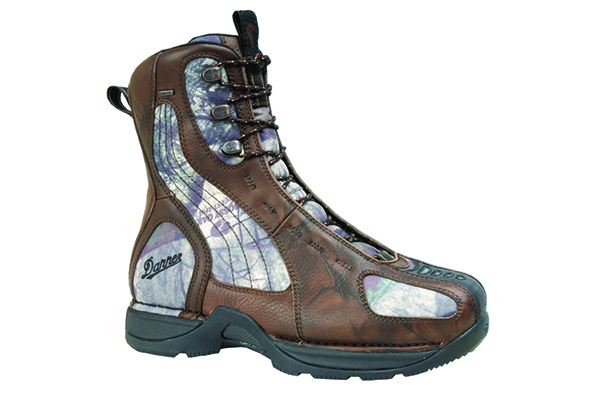

Tread designs on boots and shoes vary wildly, even if the footwear is designed for the exact same purpose. The diversity feels like it approaches one of those “grains of sand on the beach” analogies when you’re searching for a lost person in the wilderness, and our efforts—years ago, when companies didn’t materialize and vanish overnight—to create a master catalog for emergency reference were an exercise in frustration. Today’s fast-paced marketplace and proprietary designs make it worse.

Usually the best preliminary information we could gather was from the point last seen (PLS), where we could often find a clean track from which to measure and create a drawing—assuming the ground wasn’t completely skunked up with boot prints from well-meaning friends/first responders/family. Even then you could often determine a print through the process of elimination, but the phrase, “If you don’t know what you’re looking for, you won’t find it,” holds very true in tracking.

If you find yourself even slightly disoriented, it’s a good idea to take a look at the soles of your shoes, noting the distinctive pattern and unusual lugs/lines that will help make identification easier. Better yet, find a soft surface, walk over it, and come back for closer inspection. If you’re on the Appalachian Trail in Virginia and want to find your way back to a nearby parking lot, you don’t want to be following another person hiking the entire route to Maine. Back when your choice in boot soles were Vibram and Vibram, many of us deliberately cut a notch in one of the lugs to ensure an unmistakable print.

Solar Power

Tracks can be hard to see in some areas and times of the year—like autumn, when leaves can minimize print depth or obscure them altogether—making 100 yards a painstaking and backbreaking process. To minimize effort and maximize speed (regardless of conditions), avoid looking for tracks with the sun at your back. At that angle it can be impossible to see shadows cast in the footprint by the lugs and sole impressions. Don’t take my word for it. The next time you’re out find some good soil, make a footprint, back off a few feet and walk 360 degrees around the track. When it’s most visible, bend down a few inches and it should stick out like a sore thumb. Elevation isn’t a friend when you’re tracking most of the time.

Continued in Tracking Back: Finding Your Way Back To Camp – Part 2.

0 comments